The West Marches

The West Marches is an old school game type, and one very similar to megadungeons in some ways.

Unlike the megadungeon, it is a hexcrawl. Hexcrawls warrant a post of their own, but I'll give you a quick overview.

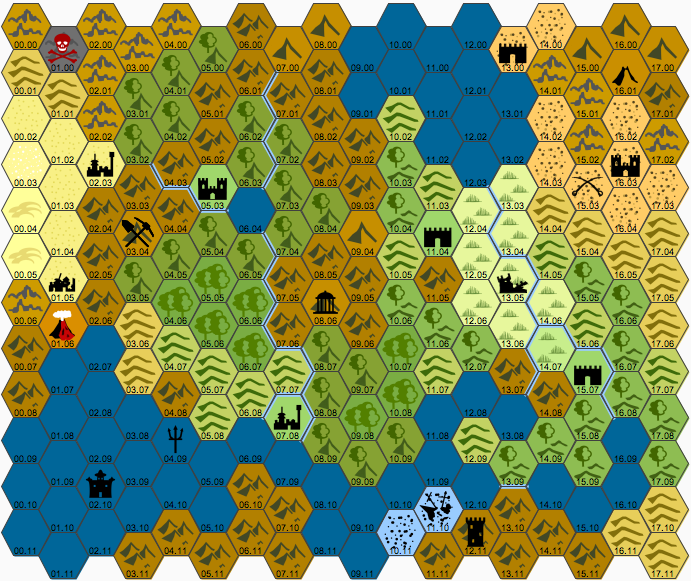

Hexcrawls are named such because you're traveling across an overworld map divided into hexes:

Each hex represents a region, along with any points of interest inside. The hex has its own geography, which plays a role in how the PCs interact with it. A desert? You have to deal with the blinding hot sun and heat, sand for miles on end. A forest? You have to navigate through all of threes and whatever beasts may lurk within them. Some may be quicker to travel through than others, so the route matters. Usually it takes a day or so to move into each hex.

The game is about exploration, peeling back the layers of the unknown and plundering what treasure and glory you can from the savage wilderness. The travel adds a separate layer to the game: suddenly things like how much you can carry, what you can eat, the weather, the environment and so forth, matter.

A hexcrawl is the ultimate sandbox game because there is no plot, just whatever emerges from your exploration. You choose a point on the map and strive to reach it, or explore a region for the surprise of discovering hidden locations. Plot emerges based on the interactions you have. For instance, you might discover a hidden temple of snake cultists, who are harassing a different region to gain tribute to their evil god. By defeating them, you open up a new region, or change the complexion of the surrounding areas. A nearby town might become friendly after you solved their snake problem. Everything is connected.

The West Marches is a subset of a hexcrawl entirely situated around the starting point of a city that serves as the "home base." It is the one point of civilization in the wilderness, from which all PCs emerge, and it is designed around the same style of pick up and play, drop-and-go rotating player bases.

Every session can sport a different group of players adventuring out into different regions, and when the session is over, the PCs return to town and experience downtime activities. When the next group of PCs moves out in the next session, it's understood the other PCs are just in town.

This means that just like the megadungeon, different adventuring parties of PCs can affect the game world for the other players. If KT's party loots a temple, then that temple is already cleared out if Aekenon gets there.

A lot of the fun of West Marches is in the implicit setting hidden in the territory; at first, there is no information, but the more you explore, the more you uncover. Some players love to keep maps of their explorations too, since the GM often hides the true world map to maintain that fog of war.

This kind of game tends to be rather challenging and dangerous, as PCs come and go. It plays into all of D&D's original core strengths: exploration, the escalation of powering up from nothing, gaining experience, loot, and so forth. Aside from that, any special plot is what the PCs bring into it, and they're pretty much interchangeable.

Because any group of PCs can come and go, it makes scheduling easier, and often player centric. The GM just has to be on standby, and when a party of players agree together that they want to basically go on a raid together, they just tell the GM and then the GM sets something up.

Naturally, games like this involve parties with different levels of players, since they can form their own groups. There is no thought given to keeping everyone on the same power level or making sure everyone gets a magic item or has a narrative scene or anything like that. The game is all about the open ended agency of the players and weighing the balance of adventure against how hard they want to push themselves.

One of the fun things about a game like this is seeing your PC put a tangible change into the game world. Defeating certain enemies or clearing our regions or meeting certain goals can have effects on the world maps and the various cities, like a game of Civilization. Sometimes you might have timeskips after a certain act was completed, showcasing a new era where the previous PCs actions essentially led to a new map.

It's also the type of game that basically never ends, so some groups of players literally get decades of IRL play out of their hexmaps.

So as you can see, it is similar to megadungeons in that it contains factions, the free association of players, and open endedness, but the fact that it takes place over a sprawling world map means a much broader explorative experience rather drilling down into a dungeon.

Oh, and it's called The West Marches, because the first guy to do this made a game where the home city was on the east side of the map representing the edge of civilization, with the entire westward region being nothing but wilderness.

If you google "D&D west marches" you'll find tons of people playing such games.